“We have already been able to convince a number of investors”

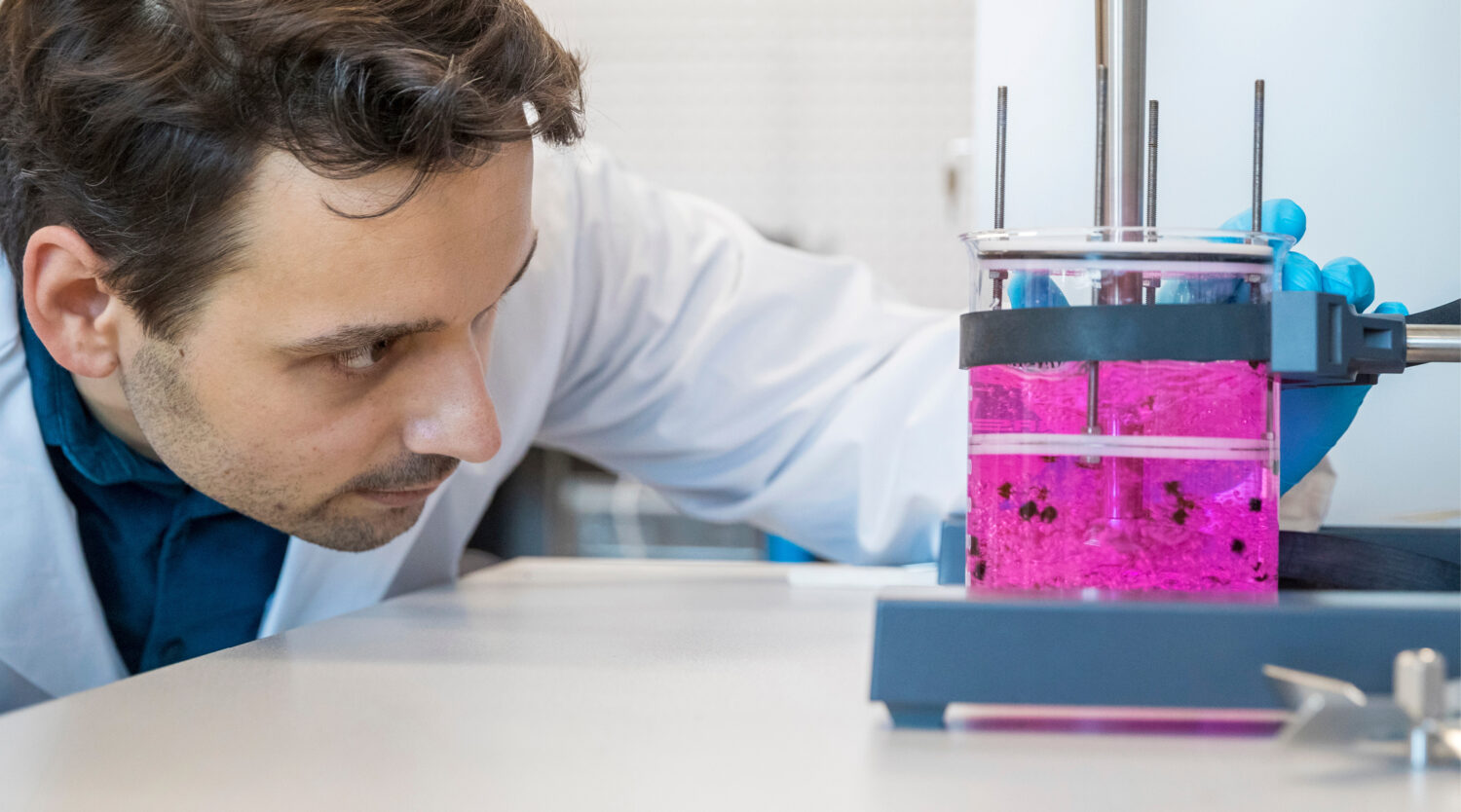

Bloom Biorenewables aims to provide companies around the world with an alternative to petrol-based products. The start-up from Marly FR is developing a technology that allows biomass to be used for the production of cosmetics, textiles and food. The CEO of the start-up Dr Remy Buser, explains why plants are the new petrol.

Dr. Remy Buser

CEO Bloom Biorenewables

Petrol is still firmly a part of our everyday lives. How do you plan to change that?

Buser: Many people are unaware that petrol, which is derived from crude oil, is found in many everyday products such as cosmetics, paints and medicines, even food. But we must replace petroleum with a sustainable material in the next 20 to 30 years. So we have developed a special technology that can extract sustainable carbon from biomass – for example, from plants growing around us. These biomaterials then serve as substitutes for the chemical industry or as fuel, which, unlike petrol comes from renewable sources. For the Innosuisse project, we restricted ourselves exclusively to wood. But the principle works with everything that grows on the Earth: grass, straw, nutshells, mango seeds, etc.

How exactly can plants be used as fuel for chemical manufacturing processes?

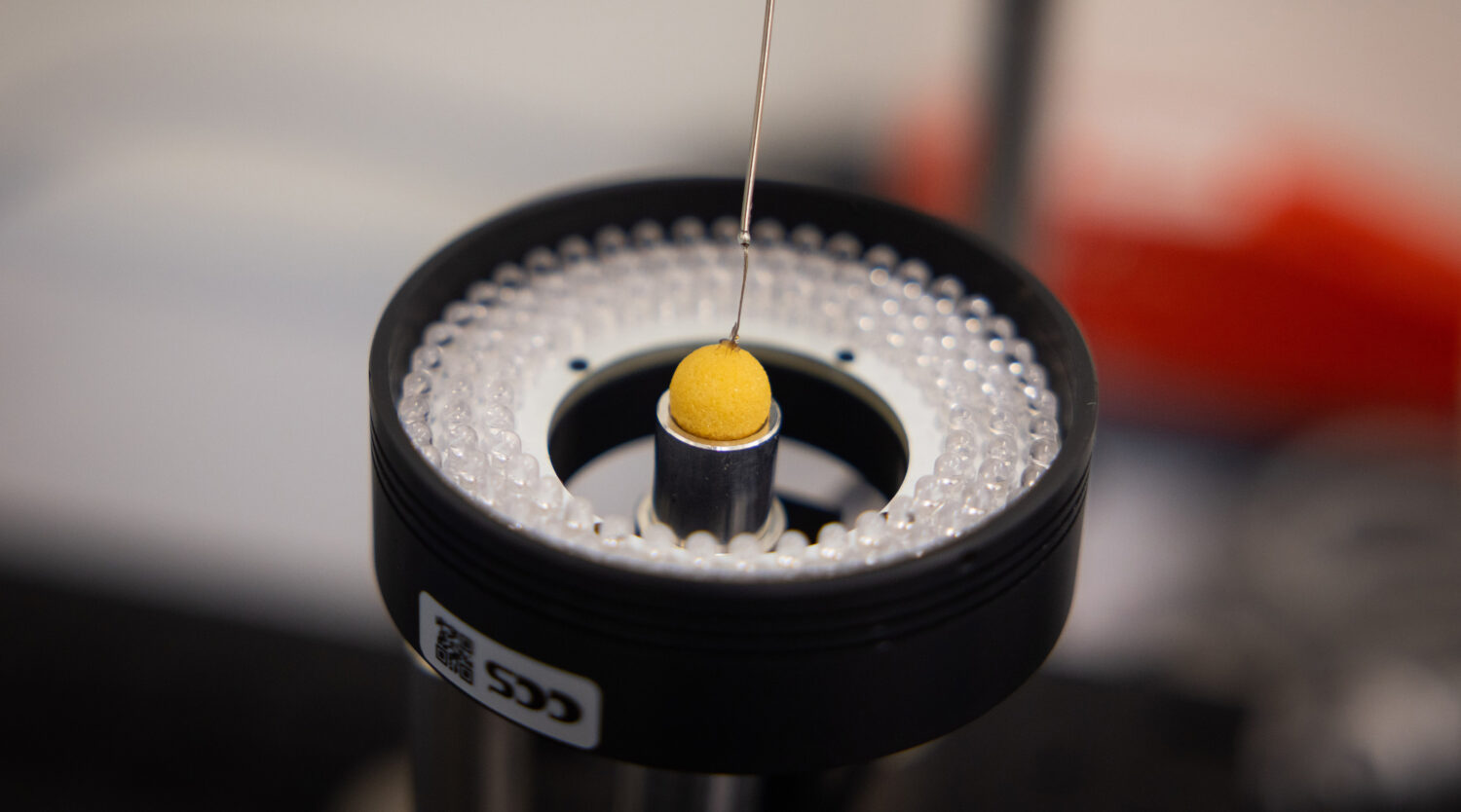

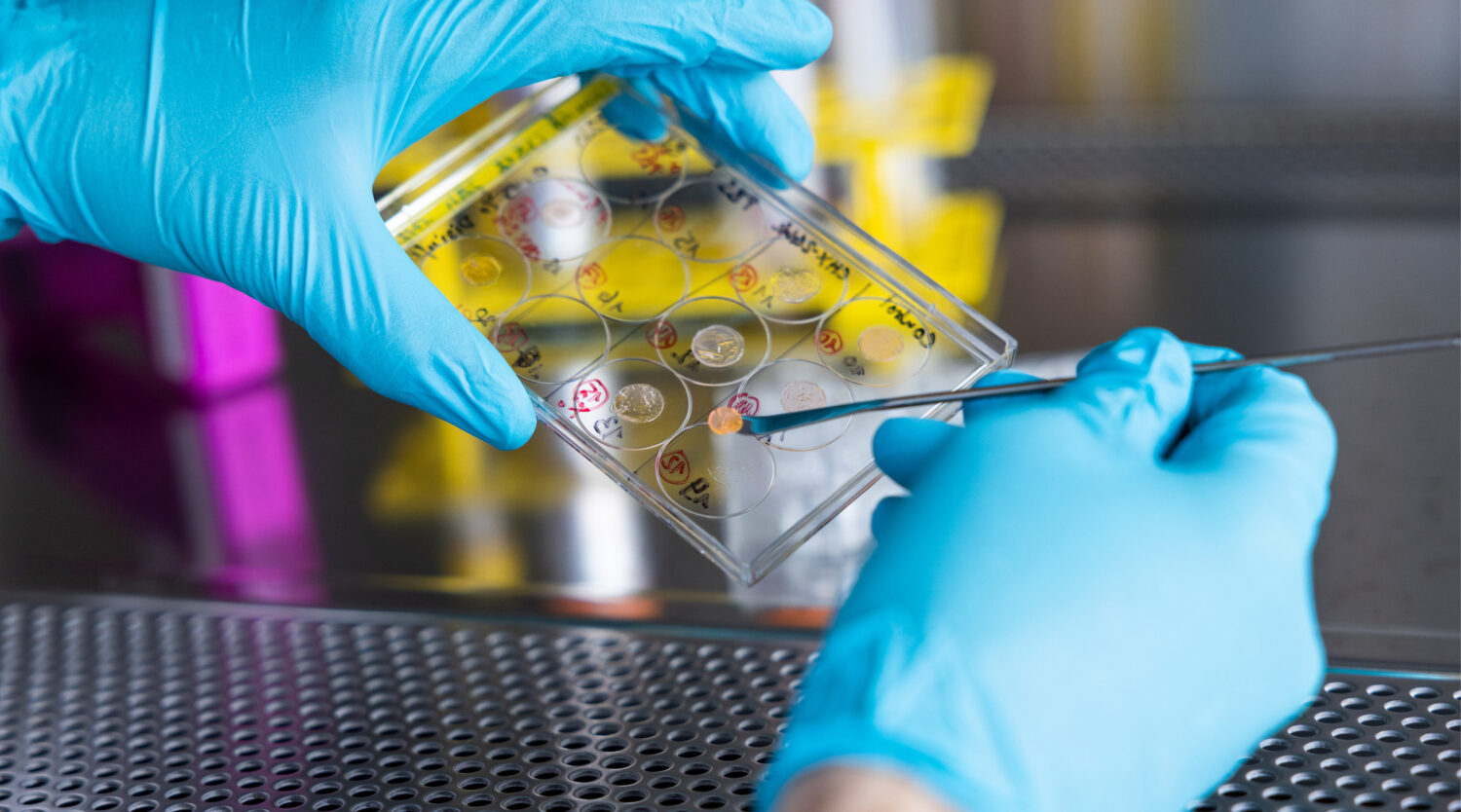

Our process breaks apart the microscopic structure of the wood. This “fractionation” is comparable to the procedure used by the paper industry, which mainly extracts cellulose from wood. For us, the most important is lignin, another component of wood. Lignin is not as well known, although it makes up a quarter of the mass in trees. Lignin has similar properties to petrol. It acts as a kind of glue and holds the remaining components of wood together.

Lignin is still barely utilised and is burned or considered a waste product. We, on the other hand, extract it and break it down to its individual basic building blocks. In a different structure, it can then be reused as a chemical building block, for example in the perfume, cosmetics, pharmaceutical and dye industries.

To give you a better idea about fractionation: imagine you have a whole egg in front of you. As an entity, it sits there hard and closed – little can be done with it. But you can do something useful with the individual components, for example, bake a cake. For that, you have to break it open. If you separate the individual parts carefully, you can do much more with them than if you hit them with a hammer. We do the same with wood. To work with its individual components, you need to proceed carefully. With our system, we can release the valuable lignin from the entire structure in such a way that it can be reused as a building block for the chemical industry.

What prompted you to research a sustainable alternative to petrol? And why did no one come up with the idea before you?

After my studies I was a scientific officer at the parliament. There, I worked primarily on environmental issues and realised that the general public doesn’t understand climate change. As a chemist, I can of course better understand the details, causes and interrelationships of climate change.

I’m concerned about it enough for me to look for solutions now. You can’t wait until everyone else finally realises what climate change is all about. That’s why we, three chemists, decided to start our own company and develop a sustainable alternative to petrol.

The analytical method to understand biomass has only really come into its own in recent years. Which is why it wasn’t possible to explore the structure of lignin before. Today we know that plants are great sources of renewable carbons.

How much did Innosuisse help you with this?

We developed the fractionation process in the laboratory two years ago, and we were able to prove scientifically that it works. However, scaling was necessary for the commercial side. To do business with the chemical industry, it’s important to produce on a larger scale.

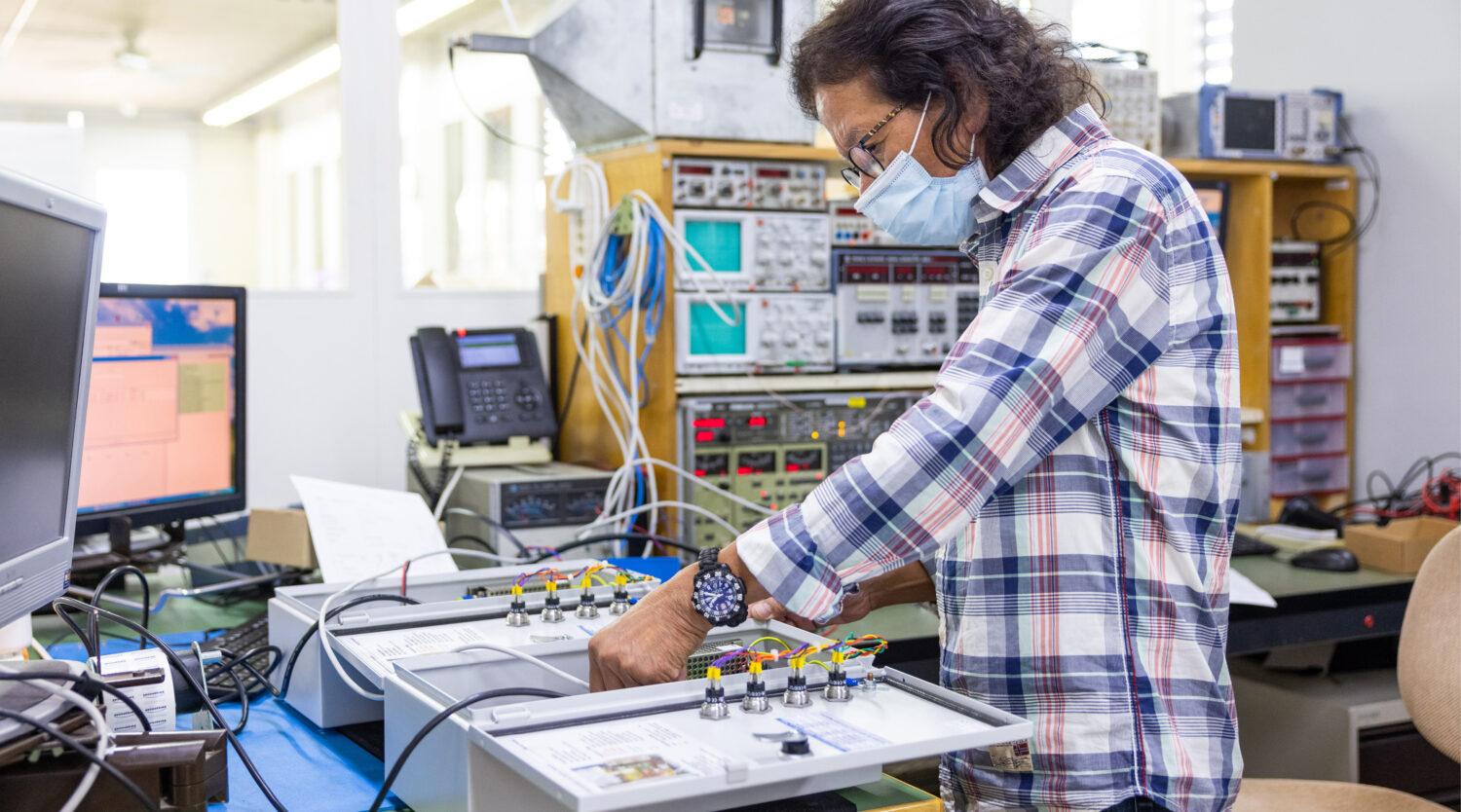

Thanks to Innosuisse’ support, we were able to collaborate with the Institute of Chemical Technology (Institut ChemTech) at the Fribourg School of Engineering & Architecture. Before the project started in 2019, we were able to extract lignin in reactors with a maximum capacity of ten litres. With the chemical plant in Fribourg, we managed to run the process in a 630-litre facility.

But scaling is a complex undertaking. Let me make another comparison from everyday life. Cooking spaghetti carbonara for four people is not the same as cooking for 400 people. You’re suddenly confronted with completely different questions: how do you drain the pasta water or mix the eggs into the sauce? The larger scale makes the process much more costly right away. The basic principle is though the same: you have to reinvent the process, so to speak, adapt the safety measures, change the procedures.

Working with the ChemTech Institute is very important to us. The expertise and the industrial dimension that the university has brought to the table has been very beneficial to us. Our company would probably not exist without Innosuisse. Their support has been essential for our economic development and has accelerated innovation.

What are your next goals?

The petrol industry is an industry of scale and works with unimaginably large quantities. With our production volume of 630 litres, we are of course still far away from being able to work commercially with our technology and persuade the industry to switch over. At present, we are continuing production with the ChemTech plant in Fribourg.

It’s the right time to find alternatives. Fortunately, we are not alone in this opinion. Thanks to the Innosuisse project, we were able to convince various investors. During 2022 and 2023, we will validate markets and seek commercial partners. Our plan is to build a larger production facility at the Marly Innovation Center (MIC), on a former Ciba-Geigy site.

Petrol has dominated the market for decades. How competitive will your product be in the future?

Many consumers have been sensitised to environmental issues and also want to live more sustainably. But for most, it is difficult to see how to do this. The subject is very complex.

And price is also an important aspect. Oil production has been around for 150 years, so all processes have been optimised. Developing a new process is, of course, more expensive. However, we cannot produce at comparable prices until we reach the same scales as the existing industry. Our models show that it is theoretically possible.

Renewable chemistry is where solar cell production was in the 1980s. Solar cells have become massively cheaper over the past 30 years.

The route to sustainable alternatives has worked in the past – and it will work again. But there will be many more companies that will have to take this journey. And not only in software, but also in hardware. Instead of digital solutions, we increasingly need alternatives for climate-friendly materials. It’s the same with electricity: to be able to use sustainable electricity, we first need to build dams and solar plants. The problem of climate change can only be fixed by hardware.

Support from Innosuisse

- Innovation cheques

- Start-up Coaching: Core Coaching

- Innovation Mentoring

- Innovation project with no implementation partner (previous project)

- 2 Innovation projects with an implementation partner (current projects)